*No spoilers below

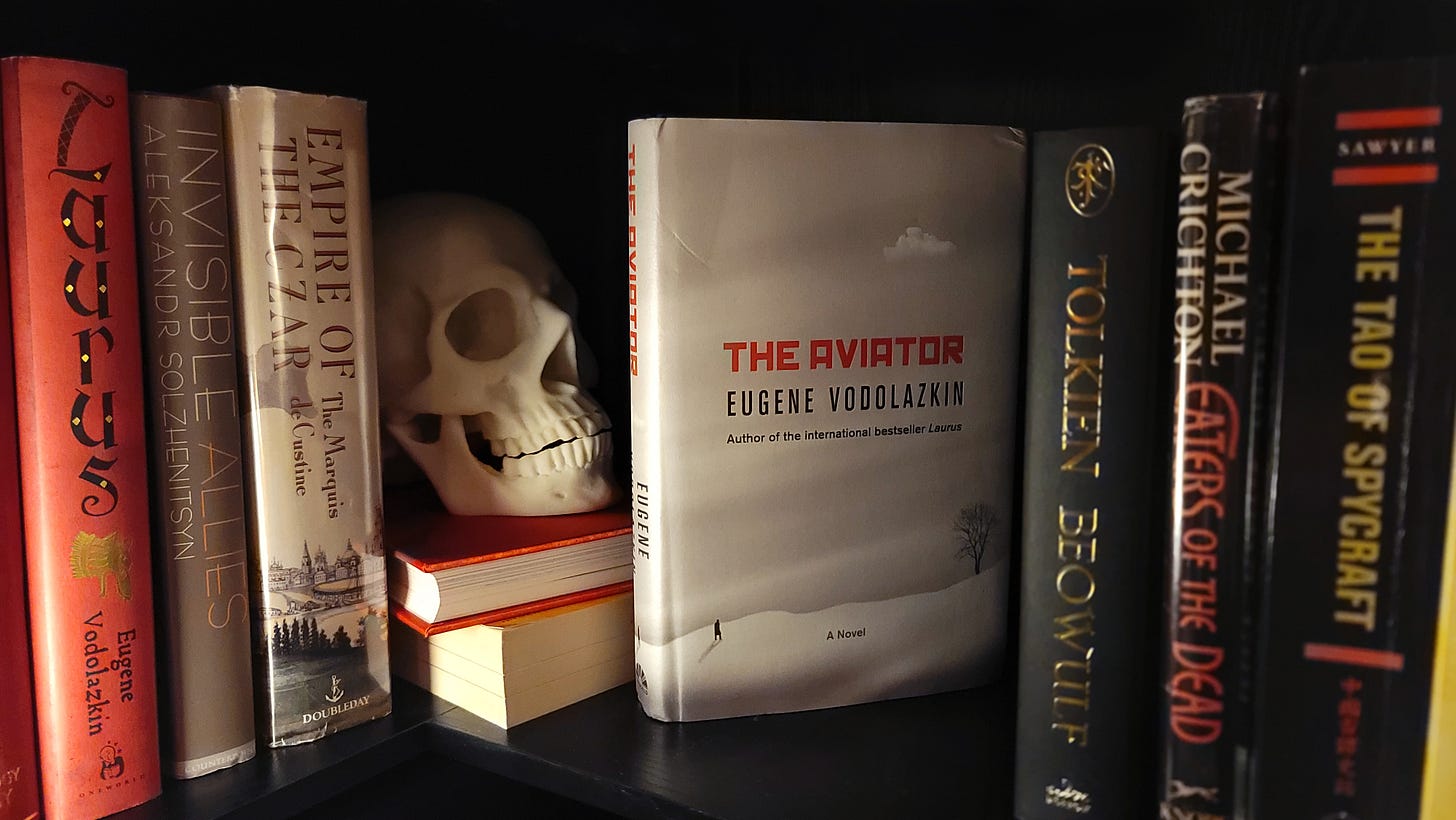

Eugene Vodolazkin occupies a unique niche in both literature in general and Russian literature in particular. As a medievalist and a man of particularly medieval faith, his approach to the question of Russia is strikingly similar to the masters of his complex nation’s particular variety of literature. There is an air of Tolstoy and, more especially, of Dostoevsky in the works of Vodolazkin that places them above humble book reviews.

As he progresses through his career, as his abilities and his themes condense, rather than broaden, his talent compresses into something very like a diamond and one begins to imagine a future in which Vodolazkin simply is a part of Russian culture.

The work of a mind such as his is not meant to be reviewed so much as studied and, more appropriately, experienced.

All this to say that it’s difficult to judge The Aviator fairly. For one thing, it emerges like a hardy bloom from particularly Slavic soil and so is different for passers-by such as myself to fully appreciate. For another, if one is reading it after Laurus, which I am, one might not experience it in the proper way. Laurus, Vodolazkin’s third novel (The Aviator is his fourth) is widely considered a masterpiece. More to the point, Laurus was precisely the type of book I personally tend to enjoy. Medieval, spiritual, profound, human. There is a richness to Laurus that is, in a sense, borrowed from the setting. A medieval setting — to me, at least — tends to be imbued more deeply with the magic of everyday transcendent mythology. An ordinary world that breathes otherness. The Aviator, set as it was in the twentieth century, could not quite capture such a miraculous setting. A world in which televisions and democratic politicians play a daily role will inevitably seem less magical in its aesthetics. And, in truth, there is very little of the magical or the miraculous in The Aviator. It soars through very ordinary skies in a very ordinary literary engine.

Yet somehow, in spite of that, something very extra-ordinary is present in its pages.

Narratively, The Aviator is not a complex story, it’s not even what I would call a structured story. Told in the form of journal entries written by our narrator, the eminently Russian protagonist Innokenty, the story reads less like a story and more like a series of images cycled through at random. One gets the impression of looking through one of those old, red View Finder toys. Innokenty has just woken from something like a coma and, as such, finds that most of his memories are gone. His doctor, the wonderfully German Geiger, assures him that these memories will return in their own time and, in the meantime, he ought to write what he remembers as he remembers it.

The prose, therefore, reads like the simple journaling of a man who is not, in terms of profession, a writer. The same phrases are repeated over and over. There is a lack of specificity or an overuse of “essentially” or “basically”; prose habits that are trained out of professional writers. Having read other work by Vodolazkin, I can say with some confidence that this was a deliberate choice. His prose is generally beautiful and poetic. The decision to write Innokenty’s entries in this less polished fashion must have been intentional. To some degree, I think this might have weakened the story. But it’s hard to judge how the original Russian had read.

That said, these snippets of Russian history, as told, in a sense, by a witness, are truly remarkable. Vodolazkin focuses not on the major events or even the major persons, but on the ordinary. Here we see Innokenty sharing a beer with a friend after a hard day’s work, here we see him playing on the beach with his timid cousin Seva. Here he is falling in love, and here he is experiencing profound loss. Here is a description of the light through the window, and here a description of the cruelties of the labor camp’s sadistic guards. A particularly striking element here is when these memories are overlaid with Innokenty’s present. A reader could predict such an occurrence in a story like this, but they never go quite the way one would expect.

As time progresses, and as more of his memory returns to him, Innokenty is able to form a more solid image of himself in his own mind. Too, he gradually comes to understand what is alluded to in the book jacket synopsis: somehow he has leapt forward in time almost seventy years. With his own most recent memories taking place in Soviet Russia immediately before the Great Terror, he is shocked to find himself in the post-Soviet Russia of the 1990s.

Around this time, also the time when he leaves the hospital, the style shifts.

Given that our hero has been displaced in time, his only human tethers to existence are the select few who have been with him since his emergence. His beloved doctor Geiger, and a woman who becomes his only family. At this point in the narrative, Innokenty’s diary entries are interspersed with theirs. This arrangement is made at the insistence of Geiger who wishes to monitor his patient with the utmost care and attention. And also with a certain German level of redundant precision.

From a reader’s perspective, there were times when this was an enlightening way to reveal plot events. For instance, we first see Innokenty perform some strange action through the eyes of the woman, then we hear from Innokenty himself what he had been doing and why, and then we hear Geiger remarking in a characteristically German fashion on both the action itself and the woman’s reaction to it. As Geiger and the woman are products of the present, while Innokenty is a relic of a strange past, these passages are fascinating examinations of the generation gap that divided Russia across regimes.

However, there were also times when this style grew tedious. One would finish reading a description of an event, only to turn the page and find oneself reading through the exact same event with little difference. And then — turn the page — and here’s one more description of the same event. My assumption is that there were cultural nuances that were present in even the tedious triplicate that were unfortunately lost on my non-Russian mind. Luckily, even if they were a bit tedious, they were rarely drawn out.

The real beauty in any Russian novel, in my humble opinion, lies in its specifically Russian philosophical nature. There are not many civilizations whose fiction output is marked by exhaustive — and not always flattering — philosophical examinations of the human condition. This is one of the reasons Dostoevsky stands out as such a giant of the genre; few other Russian novelists devoted quite as much personal energy — and narrative space — to such examinations.

I have said “not always flattering” but understand, if you would, the Russian sheen on such a thing. Russians might seem somber or even morbid, but it is precisely because of this that their faith, hope, and love are so unshakable. Few have managed, like the Russian novelist, to sift through darkness until pure, unblemished light could be found. Few, I think, understand that pure light in the way that a Russian does. Which is not to say that the rest of us cannot, but perhaps not in quite the same way. The Russian novelist takes it upon himself to understand the meaning of guilt and darkness and shame, in order to more fully understand the meaning of forgiveness, illumination, and love.

Vodolazkin does a bit of that here. His meditations come through the temporally displaced lens of Innokenty. As a man who had been born under the last czar, witnessed the October Revolution, suffered under Stalin, and then emerged in the corrupt bureaucracy of 1990s democratic Russia, he had a unique view of humanity in general and Russia in particular. His ideas, while apolitical, presented a grim condemnation of the nature of the Russian people. There is the repeated notion that a nation receives the leader it demands. Or, put another way, that a nation’s leader is a reflection of its people. The woman and Dr. Geiger did not agree, but Innokenty had witnessed the widespread uprising of the October Revolution, he had had his happiness, his family, and his life ripped away by the indifferent cruelty not of the Soviet throat-stompers, but of regular people. In his neighbors he saw reflected the image of Stalin. But, Innokenty’s friends argued, perhaps they came to reflect Stalin only after being subjugated by him, rather than the other way around.

In the end, this question is never resolved. It lingers as a perspective as unique as its speaker’s situation.

Some have remarked that the core theme in The Aviator is that love is greater than justice, a musing Innokenty writes in his journal while he considers his own guilt, as well as that of one particular camp guard who tortured him during his imprisonment sixty years ago. But I doubt this is being understood in the way it might have been intended. Innokenty, after all, had no intention of dismissing the horrors acted upon him or his loved ones during the first half of his life. But it is the love he unearths in his second life that overcomes to some degree the intense despair that had taken hold of him in the first. Not love in the romantic or even the familial sense. This love is that of the uniquely Russian kind. It is the same love spoken of by Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov. A love that embraces all and that takes upon the bearer the sins of all his neighbors. Is there forgiveness, or is there universal guilt? Perhaps there is only forgiveness because there is universal guilt, and thus there is universal love. If all are guilty, then the love that mirrors divine love is the only thing that can elevate us above the animals and the swirling, crushing cycle of human sin.

Laurus illuminated the timeless, medieval beauty of fifteenth century Rus. The Aviator shines a similar light on modern man. There does not need to be a deeper theme to this story than what one could find upon the page. This is a lovely story all on its own.

Nevertheless, the quiet power of profoundly humbling love for mankind feels timely, to some degree. Don’t misunderstand; this is not a universal love that prompts the Woodstock crowd to dust off their bell bottoms, or that insists on an erasure of all guilt. Rather, this is a love that is elevated to something akin to the Divine. “For God so loved the world…” This is a love that compels the lover to bleed and die — even if he is innocent, especially if he is not — for the good of all the world.

If there is suffering, there is also miraculous escape.

If there is loss, there is the opportunity to experience the joy of discovery.

If there is repentance, there can also be love.

If there is despair, there is always hope.

A tribute to the power of the written word in his language and yours!

Great examination! I feel the same about the Russian novelists. Currently reading Tolstoy and Solzhenitsyn