*This is a living list. I will publish addendums whenever I remember the ones I’ve definitely forgotten.

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Possibly one of the most significant and important novels ever put to paper in the history of human civilization. Yes, I know that sounds like an overstatement. But Dostoevsky’s masterpiece is just that: a masterpiece. It plumbs the depths of the universal human condition with profound insight, deep compassion, and uncommon wisdom. What Dostoevsky learned about being human from his difficult life is carefully compressed into one of the most stunning diamonds of storytelling ever produced.

Heartwarming, heartbreaking, and, most importantly, it makes you think. Not to be read quickly or skimmed. Take your time with this one and it will repay you a hundredfold.

*a note: I loathe the Pevear/Volokhosky translation. The old translation, by Constance Garnett might not, to some, read as elegantly (arguable) but it is the only one I would ever recommend. However, I’ve not been able to find a copy of her translation in print. I purchased my copy (a beautiful Heritage Press edition from 1961) on eBay. Not everyone is as particular as I am about translations, though…

(As Professor Fraus-Dolus said, “it is in the nature of languages that a pretty translation is not accurate, and an accurate translation finds its own beauty without help.”1)

Laurus by Eugene Vodolazkin

Perhaps the most extraordinary medievalist novel of the twenty-first century, and possibly one of the best novels of the twenty-first century. Profoundly Russian, in the tradition of Dostoevsky. Deeply medieval, in the tradition of Eco’s The Name of the Rose. This book accomplishes the rarest of literary feats: it manages to convey not just a tale of another time, but also the deeper sense of that time. Laurus transports the patient reader to medieval Rus in a way no other book has ever done. But it also transports the consciousness of a modern person to that of a medieval Russian. Here is the sense of timelessness, of eternity, a sense of myth and legend that is indistinguishable from everyday matters. Here is the spirit of a time that has long been lost, captured and preserved in the pages of a beautiful story.

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

Everything I needed to say about this book is here.

Collected Fictions by Jorge Luis Borges

Try as I might, I could not choose a volume of Borges’ stories that I loved more than any other. So I can only put forward for your consideration: all of them.

There is little to say about Borges that would not diminish him to some degree. To say that he writes stories would omit the sense of wonder these stories evoke. To say that these stories evoke wonder would omit the feeling that some hidden truth of the universe has been glimpsed. To say that they reveal glimpses of some hidden truth would omit the whimsical sense of narrative joy with which they were clearly written…

The notion of telling stories as if they were not fictional, was not, of course, invented by Borges, but I think anyone would agree that he perfected it. Whether it’s a biography of a fictional author or an academic examination of the various interpretations of a non-existent book, Borges proceeds with the medieval sense that everything is true. And you, hungrily reading page after page, can’t help but agree.

If you’re looking for a place to start:

The Library of Babel (obviously)

Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius

(I will update this list as I remember more of my absolute favorites, though I’ve never read one that disappointed)

A curious aside: When I was an infant (nineteen) I was on a train from Frankfurt to— somewhere, I don’t remember, it’s not important. For this train ride I had saved a new volume of Borges I had brought with me from home. And so I read one of the stories (I can’t remember which one, but for some reason I have the sense that it was Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius) and it filled me with so much wonder that I immediately pulled out my tiny little journal and scribbled away a story of my own. That story passed through several hundred iterations and revisions until it gradually became the world of Níogoln, in which I’ve set The Blue Prince.

The Gods of Pegana by Lord Dunsany

There are many who point to Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter as his important contribution to literature. But I’m afraid I have to disagree. Nothing of his has quite the magic or the wonder as his pantheon of invented gods and their strange, mystical tales.

Within this body of faux-mythology, the great god Mana-Yood-Sushai, upon finishing the creation of the small gods, fell asleep to the drumming of Skarl. And while he slept, the small gods set about making, for their own amusement, the world and all within. And should Mana-Yood-Sushai ever wake, he will wave his hand and unmake everything before returning to his own important work. (Many humans of this world include in their prayers entreaties to Skarl the Drummer to never cease his drumming, for when he does Mana-Yood-Sushai will wake.)

What follows is an astonishing collection of tales relating the duties of the various small gods and the way in which the humans of their creation interact with them.

Lord Dunsany wrote many, many collections of stories. Some revolve around the lore of Pegana and some take a Weirder — even cosmic — leaning and would likely be comfortable on the shelf next to Lovecraft. Truly a forgotten master.

Out of print. There are several decent paperback facsimiles floating around and Penguin did a collection called In the Land of Time and other Fantasy Tales. It’s not everything, but it’s a decent start.

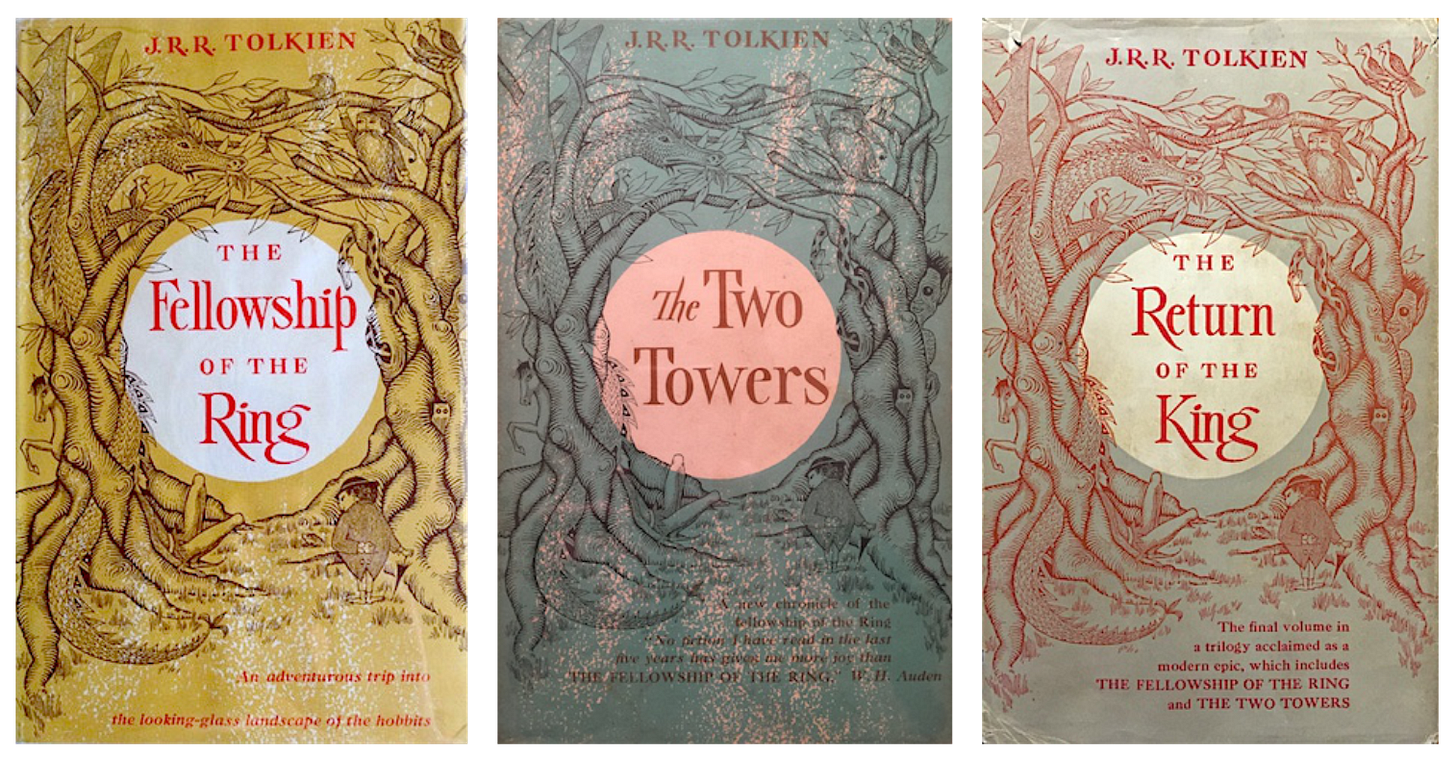

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

Obviously.

One of the most significant works of fiction of the modern age. Tolkien drew upon hundreds of years of history and mythology to craft his own version of an epic tale. The magic of Tolkien lies not in the extraordinary mastery of invented languages, nor in the breadth of his worldbuilding, but in the depth of his works’ roots. There is ancientness to Middle Earth that transcends the written work itself, transcends the maps, the lexicons, the lore, the characters. Tolkien understood the relationship of the present with the past. He understood the importance of the past and the way a culture’s roots weave through soil, home, man, woman, hearth, battlefield, and, especially, story, to provide our present with nourishment. His work accomplishes a feat that was not formerly rare but is now all but unheard of: it is an extension of something ancient and established while expressing the particular mind of its author. It is not a novelty or a revolution. It is a return to roots.

I read it for the first time when I was eleven or twelve. I remember finishing The Hobbit and crawling out of my reading nook between the couch and the window nearly on the verge of tears.

“What’s wrong?” my father asked.

“I’ve finished,” I answered sorrowfully.

“And so?”

“Now I’ll never see them again. I’ll never go with them on any more adventures!”

“There are more adventures,” my father assured me. “You just need to read The Lord of the Rings. That’s three whole books of adventures.”

“Is Bilbo there?”

“Well, no. A bit at first. But then it’s his nephew, Frodo.”

I was terribly dubious. There was simply no way I could ever love a character the way I loved Bilbo. But I tried anyway. And by the time I finished The Return of the King Frodo had become at least as important to me as dear Bilbo.

There really is nothing in the world quite like these books.

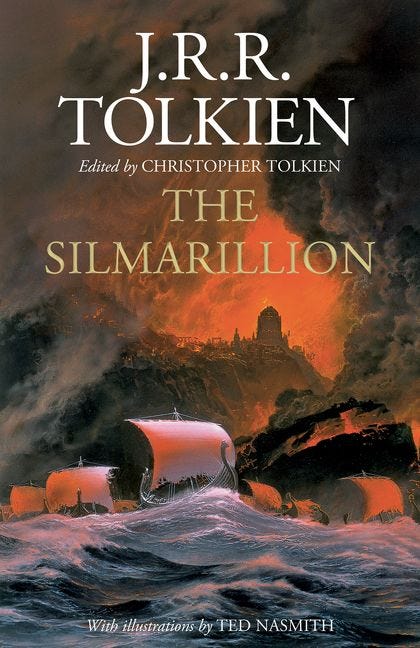

The Silmarillion by J.R.R. Tolkien

This book, in the bookshelf in my head, sits next to The Gods of Pegana. It is ancient lore, told as such. It reads like a carefully translated edition of a recently-unearthed volume of forgotten texts, the cultural history of some long-forgotten civilization that is nevertheless familiar and recognizable. It is much more interesting if you’ve read The Lord of the Rings. It isn’t really meant to be read like a novel. The chapters can often stand alone. The whole tale does come together here and there. But this is a history, and a long one. This is less worldbuilding and more an experiment in artificially-organically manufacturing an entire civilization’s ancient roots.

You’re right! Constance Garnett’s translations are superior.

I may have to put The Name of the Rose higher up my reading list. I’m in the midst of re-reading Kristin Lavransdatter at the moment, a book made much better by having read it through once already… but it’s making me crave other well-executed medievalist pieces.